Until recently trans-abdominal ultrasound was rarely used for bowel assessment due to its difficult visualisation. Endoscopy, MRI, CT, and conventional radiography were the preferred imaging methods.

However, over the past few years technological advancement and the increasing experience of ultrasound practitioners has meant that ultrasound is now an important tool for visualising bowel pathology, giving practitioners the ability to diagnose a range of different pathologies such as colorectal tumours and bowel inflammation.

My experience

In my local hospital, bowel ultrasound is now common practice as a first line and surveillance test for suspected bowel inflammation such as Crohn’s disease, providing a sensitive, safe and inexpensive diagnostic tool.

Advanced practitioners, such as myself, have developed a new role in performing gastro-intestinal (GI) ultrasound of the bowel, following training by experienced GI consultant radiologists, providing an effective and efficient service for patients.

Generally, assessment of the GI tract involves evaluating the colon, mesentery and small bowel, using both low and high frequency transducers. Assessment usually begins with initial orientation of anatomy with a low-frequency transducer, allowing for assessment of gross pathology.

Further evaluation of specific bowel segments and pathology is then undertaken using a high-frequency transducer, due to its greater resolution.

What am I looking at?

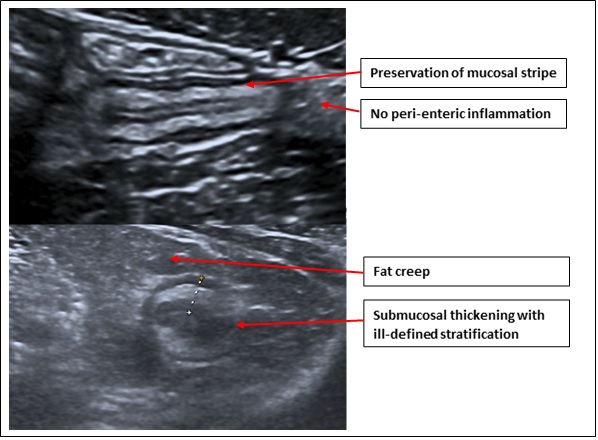

Interpretation of the bowel includes assessment of the location and appearance of the bowel, which involves the bowel wall thickness, symmetry of the wall thickness, transmural changes, motility, vascularity, mesentery, and lymph nodes.

Small and large bowel - have ultrasound characteristics that allow for a systematic interpretation of location. The colon is located framing the periphery of the abdomen with the only fixed locations being the ascending and descending colon. The transverse and sigmoid colon can differ in location and size between patients due to different lengths of individuals’ mesocolon. Small bowel is more moveable with an indistinct course, however in the majority of patients the jejunal loops can be seen within the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and the ileum can be found in the mid to right lower quadrants, with the landmark of the terminal ileum proximal to the ileocecal valve.

Luminal appearance - differentiation between small bowel and colon can be difficult due to the varying location as described. There are however, typical appearances that can aid differentiation:

- Colon is often more easily characterised by its larger calibre and is typically filled with gas and stool giving it a hyperechoic appearance.

- Colon can also be recognised with the visualisation of haustral folds.

- Small bowel can be characterised by a typically smaller luminal calibre with valvulae conniventes and fluid contents within.

- Another feature to aid differentiating small bowel is the presence of peristalsis, which is not typically seen in the colon on ultrasound due to its slower peristaltic movement.

Wall layers - A single wall layer thickness of 2mm is considered normal in a distended healthy segment of bowel. Bowel wall is made of distinct sonographic layers: lumen, mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa, with the five interfaces being visualised on ultrasound (inner-outer). The layers are distinct due to the alternating echogenicity, with the most common layers visualised being the white submucosa and the dark muscularis. The layers should be symmetrical and clear in healthy bowel, loss of differentiation can indicate pathology such as cancer and/or inflammation.

Intramural vascularity - assessment of wall vascularity with colour Doppler requires visualisation of the low velocity vessels requiring a lower pulse repetition frequency (PRF), where healthy bowel typically contains 1-2 vessel signals. Assessment with Doppler can help practitioners assess diseases such as tumours, ischaemia and inflammatory bowel disease, although it is not a particularly specific test.

Peri-intestinal assessment - assessment of the mesentery, omentum and lymph nodes can aid practitioners in the diagnosis of GI tract pathology. Assessment of the mesentery involves evaluating the clarity, size and location to aid in diagnosis of conditions such as Crohn’s disease, where fat wrapping is a characteristic appearance. Lymph nodes are common findings during assessment of the GI tract, however regional mesenteric lymphadenopathy can be useful in the assessment of physiological conditions, or suggest past/ongoing inflammation or malignant disease.

Top Tips for scanning