I have recently been reading and enjoying stoic philosophy. There is a quote attributed to Marcus Aurelius, found readily online and supposedly taken from his Meditations: ‘Look well into thyself; there is a source of strength which will always spring up if thou will always look.’ However, when I looked through my copy of the book and tried to locate the passage, I was unable to find it. Whether or not the quote is from Marcus Aurelius, it caused me think about reflective practice in my clinical placement. Consequently, I dived into my notebooks and revisited scribbled notations about how I’d ‘messed up a knee’ or ‘over rotated the wrist’.

Positive focus

A lot of these notes are underlined several times and, at the start of my placement, quite negative in their nature. As I flipped through the notebooks, they became more positive, focusing on improvements I had made or helpful tips that radiographers had shared, such as ‘ankles away, like anchors away for lateral’ or ‘consultant thanked us at the end of surgery– buzzing’ or ‘happy with chests now, rad said could do assessment – hug bucky for older patients’.

My formal reflections in my record handbook, though, are more a record of what I did in each modality. It turns out they are not reflective at all, or any reflection that is present is superficial at best. As a former teacher who is well used to a reflective cycle in practice – and having completed a module where the main assessment was a reflective essay – this gave me pause to stop and consider reflection in more detail. Whereas I thought I had been reflecting effectively, in actual fact I’d mostly just been keeping a diary. Reflection should be part of our toolkit as practitioners.

The Society of Radiographers’ Code of Conduct (2013) states that individuals should become reflective practitioners as part of their development. In fact, there is literature suggesting that embracing reflective practice has been shown to improve competence in healthcare students (McLeod et al 2020) and enable qualified practitioners to keep up with changing fields (Mantzourani et al 2019).

It has also been shown to help maintain professional competence throughout a professional’s career (McIntyre, Lathlean and Esteves 2019). All this suggests reflection is something that will help me improve so I should strive to do better with it.

Nurturing skills

Unfortunately, it has been suggested that forcing reflection on individuals will just lead to them producing a ‘desired’ reflection for an assignment, which negates the point and lessens its impact (Hobbs 2007). A way through this is to have reflective practice gradually introduced over time, to students or practitioners, enabling their confidence and skill at reflection to be nurtured (Kelsey and Hayes 2015 and Hobbs 2007).

This will require a successful modelling of reflection by experienced individuals for those learning to gain the most from it (Fletcher 1997). I know that, in my own course, reflection was the subject of one of our first assignments, and weekly reflections on our placement are a part of our documentation for clinical practice. As I said, I failed to really use reflection in a meaningful way during my clinical practice.

However, as a first-year student, I have time to embed regular reflection in my working life and really thread it through my thought process when I consider my performance. In other words, I can start small and gradually work on my reflective skills during my course, checking with mentors and lecturers to ensure that I am using reflective models correctly and self-assessing what I am getting out of the process. I have mentioned my assignment a few times already and, in researching that, I came across something with regard to reflection that I had not previously considered – its potential to help deal with the anxiety felt around placement.

Mental health

You see, there is an increase in both the rates and the severity of mental health disorders among university students, and this is specifically higher in healthcare students (Macauley et al 2018). This is probably because healthcare professionals experience higher levels of stress than those in non-medical environments (Newdrow, Steckler and Hardman 2013).

The reason for these stresses is most likely due to witnessing the tragedy, suffering and distress of people at first hand, which is something students are exposed to early on in their studies and training (Taylor 2019). This is supported by the fact that students feel the highest stress levels due to clinical practice (Wang, Lee and Espin 2019). Much of this stress is potentially ‘state anxiety’ (Cassady and Johnson 2002), which is the same kind of feeling that one might have around a test or assignment.

This contrasts with ‘generalised anxiety disorder’, which is a long-term condition where the anxiety felt is not linked to specific situations (Tyrer and Baldwin 2006). This means that some people who feel anxious about a particular scenario (going on clinical placement) might be feeling anxious more generally rather than purely because of that scenario. As anxiety is shown to affect working memory, causing issues with cognition, memory and processing capacity, this is a serious problem (Al-Ghareeb, McKenna and Cooper 2019).

There is evidence of strong links between anxiety and other conditions such as burnout and depression (Nedrow et al 2020). Reflective practice is a metacognitive exercise designed to enable individuals to address gaps in their knowledge and skills and even to reshape attitudes (Kanofsky 2020), yet it is even more powerful than that. Guided reflection has been shown to help reduce anxiety in students (Sharif et al 2013) and reflection can be used to enable individuals to look beyond just the good and bad for their practice and focus more on improving their patient-centred care (Joyce-McCoach and Smith 2016).

Realise potential

This can lead to a higher level of self-esteem in an individual and towards self-actualisation, which is the path for realisation of potential in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Sharma and Chaturvedi 2020). As a result, the ability to reflect accurately while balancing the emotions that might bring about is very important. A deep study into reflection in nursing practice listed empathy and self-awareness as two of the 11 essential ingredients for successful reflection (Clarke 2014).

This means that by developing a good, strong reflective process a student or practitioner can improve their patient-centred care by improving their empathy, technical abilities and knowledge. They can also improve their own feeling of self-esteem and confidence by being able to see their improvements and experience individual growth. This has to be seen as a positive impact on a student’s anxiety towards placement.

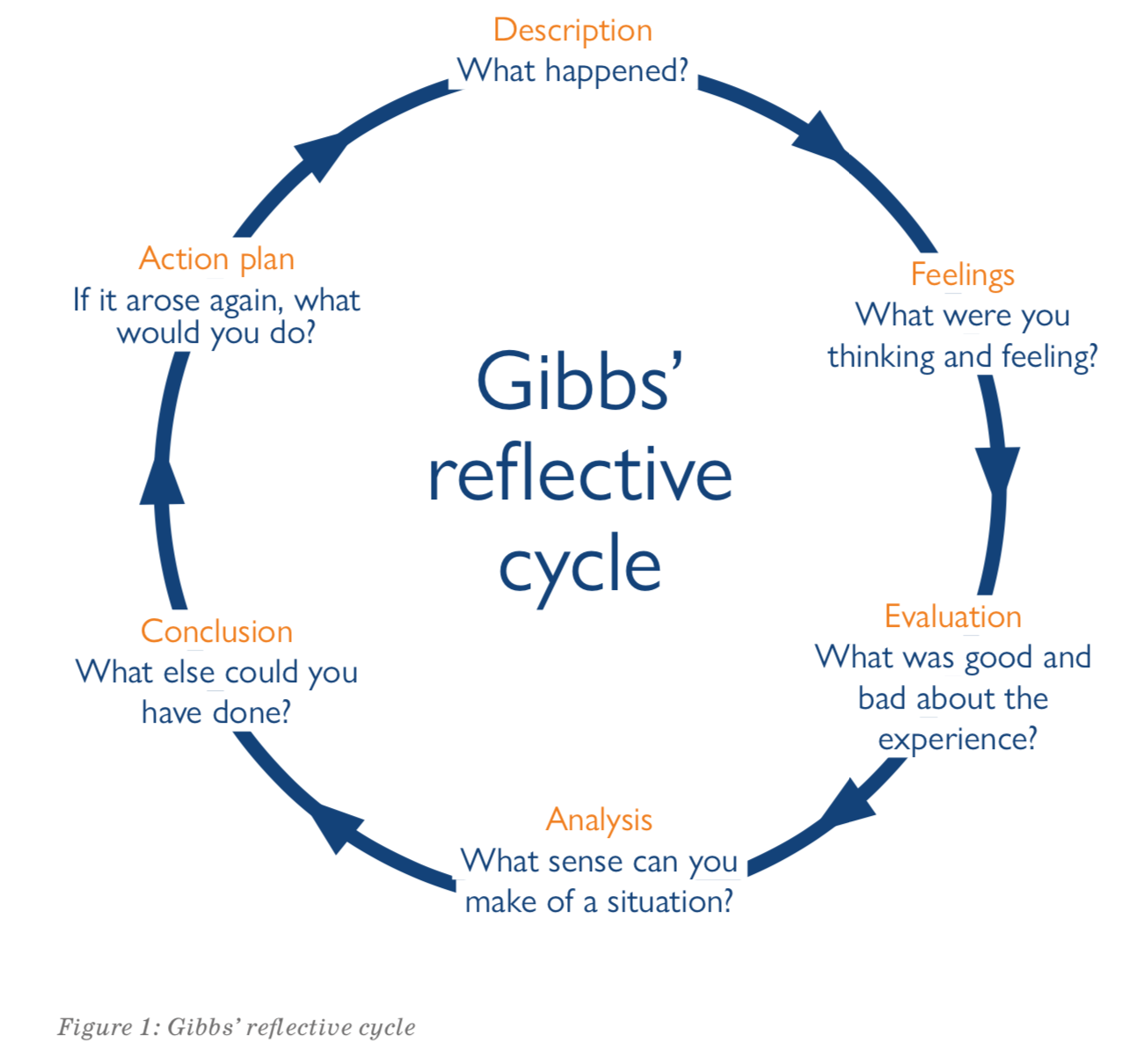

There are many models of reflection, with Kolb (1984), Gibbs (1988) and Rolfe et al (2001) being some of the main ones. Most deal in similar themes of ‘experience’, followed by ‘what happened?’ and finally ‘what will you do?’. The Rolfe model is one of the simpler versions of this, with its ‘What?’, ‘So what?’ and ‘What next?’ questions. Gibbs’ model of reflection (pictured below) is more detailed and includes focusing on the emotions felt at the time.

This, I feel, gives an important extra layer to the reflection when applied to a healthcare environment (for the reasons listed above). I used the Gibbs model in my assignment and it is the one I aim to use more in the future. However, reflection is a very personal process. It does not need to be done all the time and you do not have to follow one model (or any) of reflection.

What is important, however, is that you engage with reflection voluntarily and wholeheartedly. As Kelsey and Hayes (2015) suggest, there is a possibility that forcing practitioners to reflect using a model could cause them to reject the notion of reflection totally, which is not what we want to happen at all.

Self improvement

In short, learning to reflect on your practice effectively can help you to be a better radiographer by focusing on how you can best help patients. This is done not by thinking about what you did wrong but about how you might improve on what you previously did in a constant, non-judgmental, self-improvement cycle. In turn, this can make you feel like your role within a patient’s healthcare pathway is done to the best of your abilities, which can improve how you feel and help reduce the stress and anxiety around placement.

Personally, I’m willing to invest in reflective practice in order to be less anxious and more confident about my placement. I want to develop reflection as a tool so that I can gain the most from my practice and become the best I can be. Whether or not the words quoted at the start of this article are truly his, I would like to think Marcus Aurelius would be pleased by that thought.

Chris Gibson is a first-year diagnostic radiography student at Canterbury Christ Church University and a member of the Society of Radiographers’ Student Forum.

References

Al-Ghareeb, A., McKenna, L., Cooper, S., (2019), ‘The influence of anxiety on student nurse performance in a simulated clinical setting: A mixed methods design’, International Journal of Nursing Studies, 98, pp 57-66.

Cassady, J. and Johnson R. (2002) ‘Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance’, Contempory Educational Psychology, 27 (2), pp. 270-295, 10.1006/ceps.2001.1094 (Accessed 10 February 2021).

Clarke, N. (2014) ‘A person-centred enquiry into the teaching and learning experiences of reflection and reflective practice- Part one’, Nurse Education Today, 34, pp 1219-1224.

Fletcher, S. (1997) ‘Modelling reflective practice for pre-service teachers: the role of teacher educators’, Teaching and Teacher Education, 13:2, pp237-243.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

Hobbs, V. (2007) ‘Faking it or hating it: can reflective practice be forced?’, Reflective Practice, 8(3), pp. 405-417.

Johnson, A., Blackstone, S., Skelly, A., Simmons, W., (2020), ‘The Relationship Between Depression, Anxiety and Burnout Among Physician Assistant Students: A Multi-Institutional Study.’ Health Professions Education, 6(3), pp 420-427.

Joyce-McCoach, J. and Smith, K. (2016) ‘A teaching model for health professionals learning reflective practice’, Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences, 228, pp 265-271.

Kanofsky, S. (2020) ‘Reflective Practice of Physician Assistants’, Physician Assistant the Clinics, 5, pp 27-37.

Kelsey, C. and Hayes, S. (2015) ‘Frameworks and models- Scaffolding of straight jackets? Problematising reflective practice’, Nurse Education in Practice, 15, pp 393-396.

Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewoods Cliffs (N. J.): Prentice Hall.

Macauley, K., Plummer, L., Bemis, C., Brock, G., Larson, C. and Spangler, J. (2018) ‘Prevalence and Predictors of Anxiety in Healthcare Preofessions Students’, Health Professions Education, 4(3), pp 176-185.

Mantzourani, E., Desselle, S., Le, J., Leonie, J., Lucas, C. (2019) ‘The role of reflective practice in healthcare professions: Next steps for pharmacy education and practice’, Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15, pp 1476-1479.

McIntyre, C., Lathlean, J., Esteves, J. (2019) ‘Reflective practice enhances osteopathic clinical reasoning’, International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 33-34, pp 8-15.

McLeod, G., Vaughan, B., Carey, I., Shannon, T., Winn, E. (2020) ‘Pre-professional reflective practice: Strategies, perspectives and experiences’, International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 35, pp 50-56.

Nedrow, A., Steckler, N. A. and Hardman, J. (2013) ‘Physician resilience and burnout: can you make the switch?’, Family Practice Management, 20(1), pp. 25-30.

Nixon, S. (2001) ‘Professionalism in radiography’, Radiography, 7(1), pp. 31-35.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. and Jasper, M. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sharif, F., Dehbozorgi, R., Mani, A., Vossoughi, M. and Tavakoli, P. (2013)

‘The effect of guided reflection on test anxiety in nursing students’,

Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 2 pp. 16-20.

Sharma, M., Chaturvedi, S. and N, S. (2020) ‘Technology use expression of Maslow’s hierarchy need’, Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 48, p101895.

Taylor, R. A. (2019) ‘Contemporary issues: Resilience training alone is an incomplete intervention’, Nurse Education Today, 78, pp. 10-13.

Taylor, R. A. (2019) ‘Contemporary issues: Resilience training alone is an incomplete intervention’, Nurse Education Today, 78, pp. 10-13.

The Society of Radiographers (2013) Code of professional conduct. Available at: https://www.sor.org/learning/document-library/code-professional-conduct (Accessed 1 February 2021).

Tyrer, P. and Baldwin, D., (2006) ‘Generalised anxiety disorder’, The Lancet, 368(9553), pp.2156-2166.

University of Birmingham Gibb’s (1988) Reflective Cycle. Available at: https://birmingham.instructure.com/courses/11841/pages/gibbs-1988-reflective-cycle?module_item_id=330420 (Accessed: 20 December 2020).

Wang, A., Lee, C., Epsin, S., (2019) ‘Undergraduate nursing students’ experiences of anxiety-producing situations in clinical practicums: A descriptive survey study’. Nurse Education Today, 76, pp 103-108.